August 05, 2021 at 04:20PMMolly Ball

It wasn’t a cop bar; that was the point. They weren’t there to meet other cops. They were there to meet girls. The three police officers took seats at the wine bar in D.C.’s trendy Navy Yard neighborhood—exposed concrete walls, leather banquettes, $13 tuna tartare—and despite its being a wine bar, despite the Wednesday night half-price-wine special, they ordered beers.

May 12, 2021, was a balmy night, and dozens of newly vaccinated young urbanites mingled out on the patio. At 10 p.m., the cops asked the bartender to put CNN on the TV.

“A true American hero, officer Michael Fanone,” intoned the host, Don Lemon. “This is difficult to watch. But it is the truth of what happened that day. The truth—not the lies that you’ve been hearing.” The screen filled with Fanone’s body-camera footage from the Jan. 6 insurrection, airing publicly for the first time. “Officer Fanone is outside on the Capitol steps on the lower west terrace,” Lemon said. “This is approximately 3:15 on that day.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

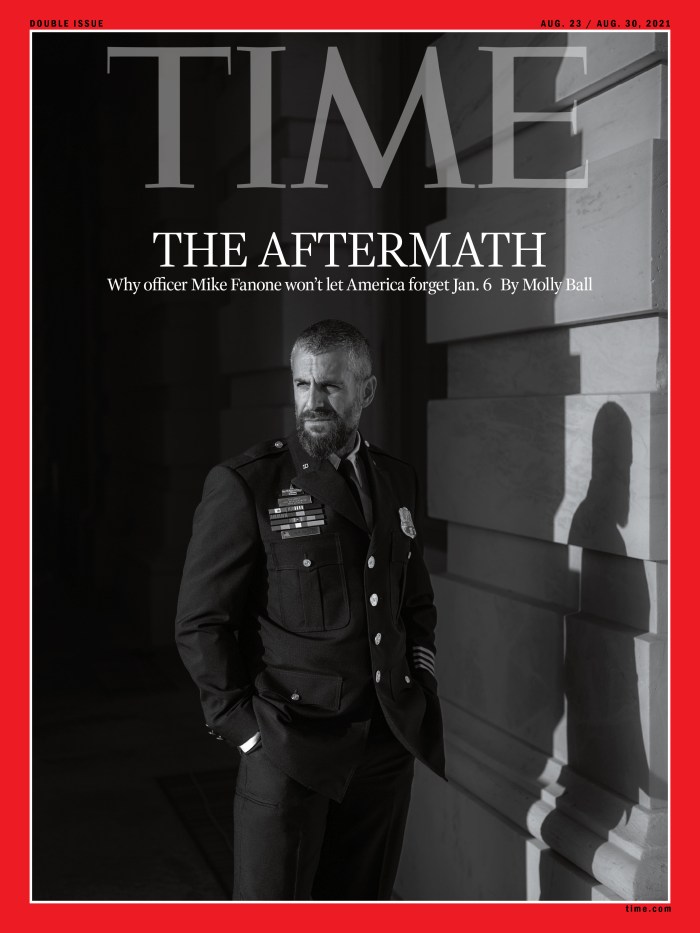

Mike Fanone—wiry, bearded, his arms and neck covered in tattoos—nursed a Modelo at the bar and took it all in again. It had been four months since the day Fanone nearly died defending the Capitol—the day a self-described redneck cop who voted for Donald Trump was beaten unconscious by a mob waving Thin Blue Line flags and chanting “U.S.A.” The day Fanone, a narcotics officer with the D.C. metropolitan police department (MPD) who’d planned to spend his evening shift buying heroin undercover, voluntarily rushed to defend the seat of American democracy and wound up in hand-to-hand combat with a horde hellbent on unstealing the election. The day Fanone was dragged down the Capitol’s marble stairs, beaten with pipes and poles, tear-gassed and stun-gunned. The day he pleaded for his life as they threatened to shoot him with his own gun, telling the rioters he had kids, until they relented and spared him.

On the TV at the bar, Fanone’s hand strained to push them away. The crush parted, and the full scene came into view: the grand terrace, the teeming crowd. Bodies upon bodies as far as the eye could see. Red hats and camo, Trump flags and American flags, all pressing forward, trying to break the cops’ tenuous hold on the central door into the building. There is a thin blue line between order and chaos, and at that moment, Mike Fanone was it.

The footage showed Fanone getting pulled out into the scrum. A man’s voice: “I got one!” Then Fanone began to scream the high-pitched, undignified screams of a man being tased in the back of the neck.

The bar fell silent as the body-cam footage played. And suddenly, for the first time since that day, Fanone was sobbing uncontrollably, shoulders heaving as his buddies put their arms around him.

Fanone—40, nearly broke, living with his mother, seeing ghosts, unable to return to duty in the only job he’d ever loved, possibly forever—had seen the footage a hundred times. But this was the first time he’d viewed it with other people, watched them witness what he lived through, see it through his eyes, feel his aggression, his valor, his abject terror. He sat there crying for a good 20 minutes. At some point he looked up and realized he was surrounded: everyone in the bar had come inside from the patio and gathered around him, watching the footage on the screen.

The months since Jan. 6 had not been easy for Fanone. Still recuperating from life-threatening injuries and posttraumatic stress disorder, he’d found himself increasingly isolated. Republicans didn’t want him to exist, and Democrats weren’t in the mood for hero cops. Even many of his colleagues didn’t see why he couldn’t just get over it. That very day, a GOP Congressman had testified that what had happened was more like a “tourist visit” than an “insurrection.” But no one could see this footage, Fanone thought, and deny what really happened that day. History would be forced to record it.

Read more: The Capitol Attack Was the Most Documented Crime in History. Will That Ensure Justice?

This is the story of what happened after Jan. 6. This is Mike Fanone’s story, recounted over weeks of searching conversations and corroborated by witnesses, public records and videotape. It is a story about what we agree to remember and what we choose to forget, about how history is not lived but manufactured after the fact. In the aftermath of a national tragedy, we are supposed to come together and say “never forget,” to agree on the heroes and the villains, on who was at fault and how their culpability must be avenged. But what happens if we can’t agree? What if we’re too busy arguing to face what really happened?

“There’s people on both sides of the political aisle that are like, ‘Listen, Jan. 6 happened, it was bad, we need to move on as a country,’” Fanone tells me one recent afternoon on the well-kept back patio of his mother’s house, between long swigs from a beer can. It’s in a quiet exurban Virginia neighborhood, ranch houses alternating with McMansions, American flags flying over big green yards. “What an arrogant f-cking thing for someone to say that wasn’t there that day,” he says. “What needs to happen is there needs to be a reckoning.”

What makes a hero? Is it bravery, charging into danger to protect others? Is it sacrifice, the damage sustained in the process? Or is it the man who refuses to let us forget?

After Fanone regained consciousness that day, he and his partner, Jimmy Albright, stumbled away from the Capitol to their patrol car, weaving like drunks from the chemical agents they’d inhaled. At one point Albright fell to his knees and vomited uncontrollably. They kept walking, arms around each other’s shoulders.

When they were almost there, Fanone said to Albright, “Dude, my neck hurts so bad.” He pulled down the collar of his black uniform, and Albright gasped:

the back of his neck was covered in pink, splotchy burns.

“Dude, what happened?” Albright asked.

“Dude, they were tasing me,” Fanone said.

Albright took a picture with his phone to show Fanone what his own neck looked like.

Fanone drifted in and out of consciousness as Albright drove to the emergency room. The security guard at the entrance told them they couldn’t go in without masks on. Albright pushed the guard aside, dragging his partner by the shoulders. At the intake counter, as a staffer was asking for his insurance information, Fanone collapsed on the floor.

The ER was jammed with a motley array of injured cops and rioters and COVID-19 patients. On the stretcher next to Fanone’s lay a rioter whose cheeks had been pierced by a rubber bullet at close range: it had gone in one side of his face and out the other. The doctors asked Fanone if he’d ever had heart problems, because his body was flooded with troponin, a chemical indicating cardiac distress. He’d had a heart attack, they told him.

From his hospital bed, he watched the news. On CNN, someone was questioning whether the police had used sufficient force to repel the rioters, asking why they hadn’t arrested more people on the scene. Outraged, Fanone looked up CNN, called the number that came up on his phone and told the woman who answered that Mike Fanone with the metropolitan police department needed to talk right away to that jerk on the air who was insulting the good name of every police officer.

“Sir,” she said, “this is the front desk.”

He burned to set the record straight, and he soon got his chance. A photo went viral in the days after the riot: Fanone in his helmet and tactical vest, face distorted in a furious battle grimace, the lone cop in a sea of rioters, Thin Blue Line flag waving ironically over his head. His ex-wife, the mother of his three youngest daughters, proudly posted his name on social media, and suddenly everyone seemed to have his number.

The following week, at his urging, the department set up a round of interviews with the Washington Post and major TV networks. Fanone, one of several officers authorized to speak to the press, was the star of every segment. “They were overthrowing the Capitol, the seat of democracy, and I f-cking went,” he said, neck tattoos peeking from his collar. He was pugnacious, funny, charismatic, unfiltered. The battle, he quipped, felt like the movie 300, “except without the six-pack abs, which none of us have.”

Perhaps most indelibly, Fanone offered his take on the rioters who’d heeded his pleas for mercy. “A lot of people have asked me my thoughts on the individuals in the crowd that helped me,” he drawled. “I think the conclusion I’ve come to is, like, thank you”—here he paused and squinted—“but f-ck you for being there.”

The response was overwhelming. Thousands of letters, tens of thousands of emails, poured into the MPD. Men wanted to thank him. Children said they looked up to him. Women swooned. (Fanone turned down a request to pose nude in Playgirl.) Liberals posted worshipful memes. Joan Baez, the singer and activist, made an oil painting of his face and captioned it: “Thank you, but f-ck you for being there.” At a gas station at 5 a.m., an elderly Black woman walked up and said, “Are you Michael Fanone? Can I hug you?” and burst into tears as he held her in his arms.

People were hungry for heroes, hungry for a sliver of humanity in the ugliness and violence. Here was the brave cop who rushed into danger and put his life on the line for his country. He was embarrassed by the attention, but it also seemed right on some level, like America agreed that what happened at the Capitol was an attack on all of us, like we were coming together to denounce the bad guys and lift up the good.

But the story was only beginning.

The House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings against Trump for inciting the riot, and the Democratic lawmakers managing the impeachment reached out to Fanone for help putting together their case. He met House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and shocked her with his foul language. On Jan. 13, 10 Republicans joined the Democrats in voting to impeach Trump for a second time. Fanone called each of their offices to thank them.

The 10 Republicans invited him to meet at the Capitol Hill Club. They hailed his heroism—and told him they feared they’d just ended their political careers. Death threats were pouring in from their pro-Trump constituents. Right-wing activists were lining up to unseat them in primaries. It didn’t make sense to Fanone that there were only 10 of them. Hadn’t all the members of Congress been there that day? Hadn’t they fled the chamber in terror as he and his colleagues held off the mob? The Republicans told him that plenty of their colleagues privately agreed Trump was to blame, Fanone says. But they didn’t want to commit political suicide.

Read more: How Trump’s Effort to Steal the Election Tore Apart the GOP—and the Country

At the same time, Fanone had questions about the investigation into the assault he suffered. MPD detective Yari Babich had been assigned to the case, but Fanone learned Babich had posted a bunch of nasty comments on social media about Fanone’s media tour—calling him an egomaniac, a celebrity wannabe, unprofessional, a buffoon. Fanone complained to the department but says he was told Babich was entitled to his opinion. (In response to a detailed list of written questions, the MPD declined to comment on this or other aspects of this story. TIME was unable to immediately reach Babich for comment.) He kept complaining, and eventually Babich was taken off the case, according to law-enforcement officials familiar with the matter. But cops gossip like hens, and Fanone knew that if one guy was talking this way he probably wasn’t the only one. Fanone had thought that in telling his story he was speaking for all of them, helping them get the recognition they deserved. What if other cops didn’t see it that way?

After two weeks, the adrenaline that carried him through Jan. 6 and the immediate aftermath started to wear off. His phone stopped ringing. He wanted to go back on TV and respond to the lies Trump and his acolytes were telling, but the department’s public-information officer told him the mayor’s office was not authorizing any more interviews.

Fanone’s head hurt constantly. Everything seemed to be rushing at him all the time; he needed to be somewhere quiet. The doctors told him he had PTSD. He’d be going about his day, and suddenly the idea that he would be better off dead would appear in his mind. He didn’t know how to shake it. Then it would just as suddenly be gone, until it came back again.

Anger alternated with self-doubt. He kept watching the video footage, but instead of feeling proud, he started picking it apart. The famous photo—what if what people saw on his face was not bravery but fear? How had he let himself get pulled into the crowd, away from the group? Was it his fault? What more could he have done?

In February, Fanone and a couple of other officers were invited to the Super Bowl. The police chief persuaded him to go on behalf of the department, telling him it would prove that the nation could still rally around law enforcement. The officers were told there would be a ceremony at halftime, Fanone says—a solemn procession of honor and reverence, the sort of thing we do to create heroes in America. But at the last minute, the officers were told to leave their uniforms at home. While the game featured elaborate tributes to health care workers and to racial justice, the cops got only a brief callout from the announcers as they were shown in their box midway through the third quarter. (The NFL denied the officers were promised an on-field ceremony.)

He was a good cop—one of the best. Fanone was born in the District and raised in Alexandria, Va., his father a lawyer, his mother a social worker. They divorced when he was 8. His dad was a partner at a big firm, but Fanone hated the stuffy status-grubbing of fancy-pants D.C. He spent his free time with his mother’s working-class family in rural Maryland, boating, fishing, crabbing, hunting and watching John Wayne movies. “Michael was a cowboy from the time he was 3 years old,” says his mother Terry Fanone.

Attempts to smuggle the self-styled backwoods boy into the professional class were unsuccessful. He spent a year at Georgetown Prep, the private school whose alumni include two U.S. Supreme Court Justices, but was asked not to return. When his parents sent him to boarding school in Maine instead, he saved his pocket money and bought a bus ticket back home. After his parents kicked him out, he got a job working construction and eventually completed his high-school diploma at Ballou, a nearly all-Black public school in southeast D.C.

Fanone joined the Capitol Police shortly after 9/11, but he knew by the time he finished at the academy that he didn’t want to spend his career there. Fanone and his buddy Ramey Kyle would drive down to the projects on their lunch break and chase drug dealers, to management’s chagrin. “We were 21-, 22-year-old adrenaline junkies—we wanted to run and gun,” Fanone recalls. After a couple of years, he and Kyle both moved to the MPD.

Fanone loved the job—the thrill of it, the intensity, the brotherhood of officers. He recalls the rush of pulling up to the projects and watching people scatter. Gradually he honed his skills, working with informants, establishing probable cause, liaising with federal agencies on wiretap cases and big busts. He studied local defense attorneys and relished sparring with them on the witness stand. “He went from being this wild and crazy, reckless guy—that was his image at the beginning—to thinking things out and planning ahead and being meticulous,” says Jeff Leslie, who was Fanone’s partner for more than a decade. “Mike is the best narcotics officer I’ve ever worked with, including FBI and DEA.”

At some point in his 30s, Fanone realized there was more to life than the job. His mentor, someone he thought of as a living legend, retired, and there were no parades—the department just carried on without him. Fanone stopped volunteering for overtime and re-established contact with the teenage daughter he barely knew. He got married, had three more daughters, got divorced.

<strong>“If I didn’t speak out against Trump, would people think I was just another evil white cop?”</strong> He wasn’t interested in politics—it should be, he thought, like the Olympics, something to gawk at every four years and then put away. But for a white cop who spent his time policing Black neighborhoods, politics became harder and harder to ignore. He hated the way liberal politicians and the media always made police the bad guys. After the 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., people seemed to assume every cop was like Darren Wilson, the white officer who shot Brown. Of course there were bad cops, but they weren’t all like that. The city council kept making new rules about what they could and couldn’t do. He did his best to follow the blitz of reform-minded dictates from above: community outreach, sensitivity training, de-escalation. He took to heart the ideas about better rather than more arrests, he says, only to be penalized for not arresting enough people. Tired of anti-police sentiment and feeling a bit of kinship with the bombastic, abrasive politician, Fanone voted for Trump in 2016.

But with Trump in office, policing in America only became more fraught. Jeff Leslie spent the summer of 2020 working 12-hour days at the George Floyd protests in D.C., standing stoically on the sidelines as white kids from the suburbs spat in his face and called him a racist. The very first day, a brick went through his cruiser window and a Molotov cocktail nearly lit it on fire. “I said to some of these white guys in antifa gear, ‘Look, you’re more educated than me, and I do believe you care about Black people,’” Leslie recalls. “‘Let me take you down to the hood and show you how you can really invest in some young Black lives.’” The law-abiding citizens of those neighborhoods weren’t calling to abolish the police, Leslie says; they told him they wanted more police to clean up their community. None of the protesters ever took him up on his offer.

Leslie was there on Jan. 6. He was in the battle with Fanone and got hit with hammers. But he’s suspicious of Fanone’s new liberal friends. “I love the guy, and I’m concerned that all those people are using and manipulating him,” Leslie says. “He’s always wanted us to be respected and appreciated for what we do, and it’s never going to happen. We’re never going to get a parade. No one cares. Now all these people want to use him against Trump. But these are still the same people calling us white supremists and saying we should be defunded.”

Fanone shares that worry: “If I didn’t speak out against Trump, would people think I was just another evil white cop?” What he hoped to make people understand was that he wasn’t some exceptional “good cop”—he was every cop. The worst kind of cop: the arrogant adrenaline junkie. And the best kind of cop: meticulous, humane, committed. Maybe the liberals who supported him would see they ought to support the others too—the hundreds who answered the call at the Capitol; the thousands who rush into danger every day for the sake of their ungrateful asses.

Because Fanone was just like every other cop. Unless, after Jan. 6, he wasn’t.

Andrew Clyde, a first-term Republican representing Georgia’s Ninth district, witnessed more of the Jan. 6 chaos than many of his colleagues. Around the time Fanone was getting tased on the Capitol terrace, as most members of Congress were being whisked to safety, Clyde, a 57-year-old former Navy aviator and gun-shop owner, bravely helped barricade the door to the House chamber as rioters massed outside.

Yet Clyde soon became a case study in the GOP’s determination to forget. On May 12—the day Fanone broke down at the bar—Clyde insisted in a House hearing that the footage from Jan. 6 resembled a “normal tourist visit” more than the coup attempt liberals portrayed.

Something broke open inside Mike Fanone when he heard Clyde’s comments. His courage, his fists, his neck, had kept these guys from being strung up, and now they wanted to pretend it never happened? How could they deny it when it was all right there on video? Fanone couldn’t let these cowards keep twisting the facts. The department’s press officer had stopped answering his calls. He didn’t care. He’d gone rogue.

But the Republicans weren’t the only ones who wanted to put Jan. 6 behind them. A new President had taken over, promising to heal the nation’s wounds, and the public had turned its attention to the future: the pandemic ebbing, Congress passing laws. Fanone wrote a letter to every politician he could think of, demanding to know why the officers who fought that day hadn’t been recognized. The White House acknowledged the letter but never got back to him; the mayor’s office did not respond. (A spokesman said the White House was still in the process of responding to Fanone’s three-month-old letter. The mayor’s office noted that the officers were subsequently honored at an employee-appreciation ceremony.)

Fanone’s new political friends told him not to take it personally. That President Biden was trying to “lower the temperature” in the country. That D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser couldn’t be seen as too pro-police in the current political climate. He wasn’t being slighted, they told him; he was just politically inconvenient.

In Congress, official honors for police who defended the Capitol were caught up in legislative squabbling. The Senate voted in February to award the Congressional Gold Medal to Capitol Police officer Eugene Goodman, who’d led a mob away from the Senate chamber as Senators evacuated. But the House wanted to give medals to all the officers who were there. Months of back-and-forth ensued.

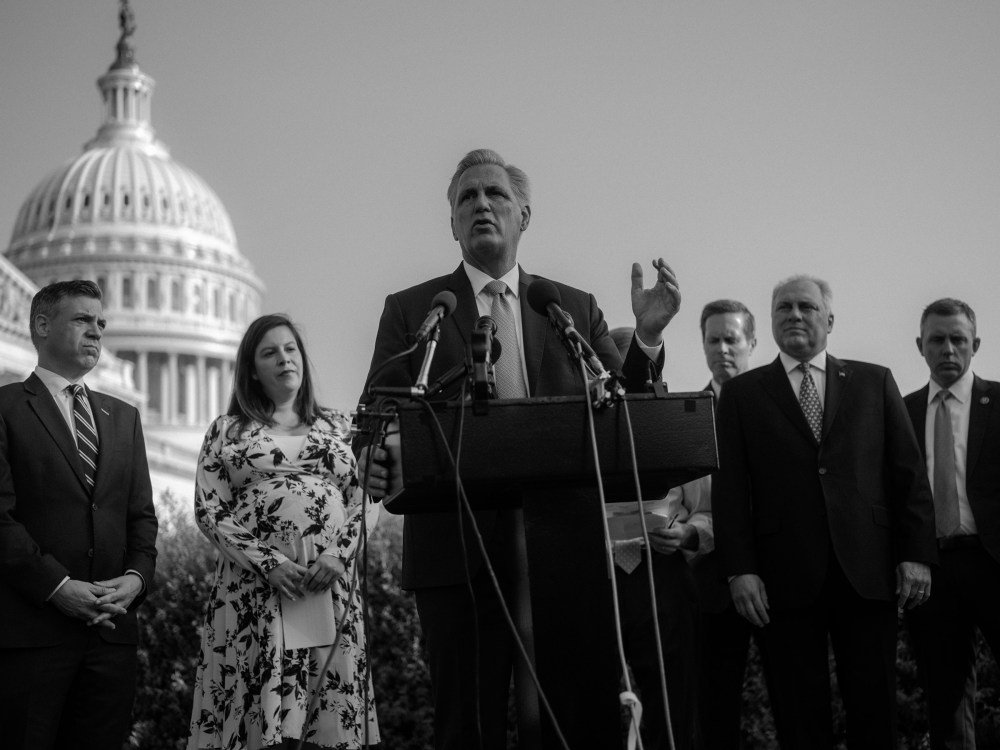

Democrats and Republicans feuded over how to investigate Jan. 6. Bipartisan negotiations to establish an independent, 9/11-style commission looked promising until the House and Senate GOP leaders, Kevin McCarthy and Mitch McConnell, torpedoed the talks. In the days after the riot, McCarthy had said Trump bore responsibility for it and McConnell had passionately denounced him. Now they had an upcoming election to worry about.

Read more: The Start of the Jan. 6 Insurrection Inquiry Shows Its Stakes—And Its Shortcoming

On June 15, the House finally passed legislation awarding gold medals to the Capitol Police and MPD for their valor on Jan. 6. Twenty-one Republicans voted against it, including Clyde. Fanone decided to pay each of them a visit. He and Capitol Police officer Harry Dunn, a 6-ft. 7-in. Black man who’d spent Jan. 6 herding rioters on an interior staircase as they hurled racial slurs, went to each of the 21 lawmakers’ offices, politely requesting to schedule appointments. But the only one they met that day was Clyde.

Fanone spotted him getting into an elevator, and he and Dunn followed Clyde in. “How are you doing, Congressman?” Fanone said as the doors closed, putting out his hand.

Clyde shrank away. “You’re not going to shake my hand?” Fanone said.

“I don’t know who you are,” Clyde said.

“I apologize,” Fanone said, and launched, for the umpteenth time, into his practiced spiel. “My name is Michael Fanone. I’m a D.C. metropolitan police officer who fought on Jan. 6 to defend the Capitol, and as a result I was significantly injured. I sustained a heart attack and a traumatic brain injury after being tased numerous times at the base of my skull, as well as being severely beaten.”

Clyde turned away and started fumbling with his phone. The elevator doors opened, and he bolted. (Clyde later issued a statement acknowledging the elevator encounter but said he did “not recall [Fanone’s] offering to shake hands.”)

Fanone called his new friend Eric Swalwell, a Democratic Representative from California, and told him what had just happened.

“What do you want me to do?” Swalwell asked.

“Tweet it, motherf-cker!” said Fanone, who eschews social media.

Swalwell and another friend, Republican Congressman Adam Kinzinger, both tweeted about the incident. Fanone went on television and called Clyde a “coward.” The story was all over the news. He had fought back against the lies with the force of his truth, and for a moment, he believed he had won.

But the rot was setting in—the fatigue, the forgetting, the whitewashing. Trump claimed Jan. 6 was not a riot but a “lovefest,” that the rioters’ interactions with police that day were more like “hugging and kissing.” Newsmax did a segment portraying Fanone as a mentally ill anti-Trumper; one of the network’s anchors called him a “crybaby” and an “unhinged gangbanger.” QAnon zealots in private forums whispered that he was a paid actor, not a cop at all. Republican Congressman Paul Gosar called the police shooting of Ashli Babbitt—a rioter who was attempting to force her way into the Speaker’s Lobby off the House floor—an “execution.” Polls showed that more and more Republicans saw the attack on the Capitol as a display of patriotism.

In meetings with GOP members of Congress, Fanone asked how they could claim to “back the blue” while selling him out. They brought up Black Lives Matter and how they’d had the cops’ backs. “You guys don’t seem to have a problem when we’re kicking the sh-t out of Black people,” Fanone recalls saying. “But when we’re kicking the sh-t out of white people, uh-oh, that’s an issue.” He found himself explaining why attempting to overthrow a CVS was slightly different than attempting to overthrow the government. Why the peaceful transfer of power was a bigger deal than a few anarchists in Portland, Ore.

Conservative pundits quibbled with the riot’s body count, pointing out that Capitol Police officer Brian Sicknick, who died the day after he helped fight off the rioters, had technically passed away of “natural causes” after a series of strokes. Fanone had gone to the Capitol to see Sicknick’s body lie in honor, buying his only suit for the occasion. He’d gotten to know Sicknick’s mother and girlfriend. (All of them, incidentally, were Trump voters.) Is that what they’d be saying if I didn’t make it? Fanone wondered. That he’d died of a heart attack? That it wasn’t Trump’s fault, just “natural causes”?

Fox News hosts invented other explanations for the violence: antifa provocateurs, FBI infiltrators. Tucker Carlson called Dunn “an angry left-wing political activist” who could not “pretend to speak for the country’s law-enforcement community.” Fanone wanted to go on Fox News to argue but, he says, a booker told him there was a networkwide ban on his appearing. (A Fox News spokesperson denied this.)

<strong>“The vast majority of police officers—would they have been on the other side of those battle lines?”</strong>Much as he hated to admit it, Fanone was starting to suspect Carlson had a point. Maybe officers like him and Dunn, who wanted Trump held accountable, were the exception. Watching the body-cam footage again, he noticed how many cops were standing around, kibitzing with the rioters. He thought of his MPD colleagues: out of more than 3,000 on duty, about 850 had responded to the Capitol. What about all the others?

Where was his backup? Where was the police union, which rushed to the defense of any officer criticized by left-wing politicians? The Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), which endorsed Trump in 2016 and 2020, had issued a lukewarm statement on Jan. 6 urging “everyone involved to reject the use of violence and to obey the orders of law enforcement officers to ensure that these events are brought to a swift and peaceable end.” Numerous active-duty FOP members have since been charged in connection with the riot. In at least one case, the union is trying to keep an accused rioter from being fired by his department.

There was an FOP meeting on July 14, and Fanone and Dunn decided to attend. Fanone arrived with specific demands. He wanted a public condemnation of the 21 Republican lawmakers who’d voted against the gold medals. He wanted Clyde and Gosar condemned specifically, and he wanted the officer who shot Babbitt defended as forcefully as the FOP had defended officers who shot Black citizens in the past. Fanone addressed the FOP’s national president, Patrick Yoes, an ardent Trump supporter. “You are doing a disservice to your membership by not speaking the truth of that day,” Fanone said. “You have an opportunity to educate Americans—not just police officers but Americans—about what actually happened, and you’re not doing it.”

Yoes bristled. He told Fanone the only thing he could offer was access to the FOP’s free wellness program. (In an interview, Yoes said the FOP hopes to work with Fanone and his local union to resolve his complaints. “I see his struggles, I see he is dealing with a lot, and he may have some misconceptions about it,” Yoes says, “but I assure you we have been there for him and will continue to be.”)

At the end of the meeting, the D.C. lodge voted to endorse Yoes for another term as union president.

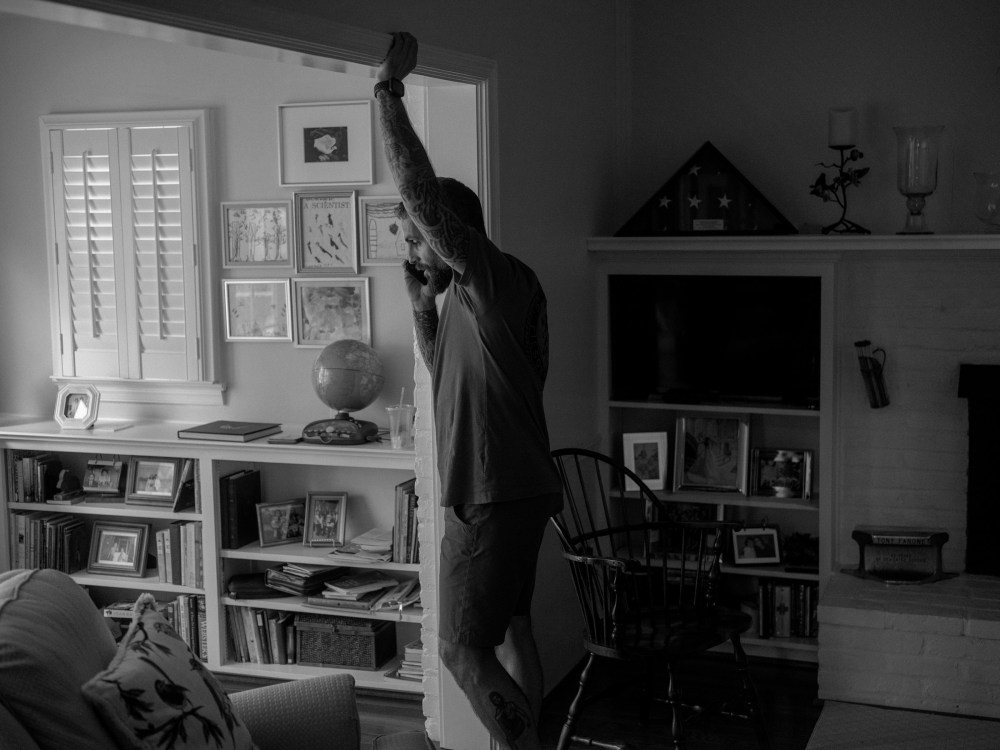

Healed from his physical injuries but still on mental-health leave, Fanone now spends most days alone. He goes to the gym, takes care of his daughters part time, fields media calls. He probably can’t go back to undercover work, and he wonders if he’d be safe going back on the job at all. Colleagues he’s known for decades don’t talk to him anymore. Guys who never called to check in when he was in the hospital send him taunting memes about his liberal-darling status.

“I had convinced myself, Mike, you’re vocalizing the opinions of thousands and thousands of police officers. But I’m starting to think I’m vocalizing the beliefs of just one,” Fanone says one day over lunch, as his three young daughters dig into their chicken tenders. “While there are still some officers that are very supportive of me, I can count them on one hand. The vast majority of police officers—would they have been on the other side of those battle lines?”

His mission to defend his colleagues’ actions had morphed into something bigger and more daunting. What he had to do, he concluded, was not just to speak up on behalf of law enforcement. He needed to shake his fellow Americans out of their Trump-induced delusions, debunk the lies that had poisoned his friends’ minds. He needed to root out the hatred that led to Trump in the first place.

“The greatest trick in history was Donald Trump convincing redneck Americans that he somehow speaks for them,” says Fanone, who includes himself in that category. “He will destroy this country simply for the sake of his ego, just because he can’t accept that he lost an election.”

In late July, Fanone was one of four officers who testified at the first hearing of the House committee investigating Jan. 6, a proceeding that just two Republicans took part in. “The indifference shown to my colleagues is disgraceful,” he cried, pounding the table. A Fox News anchor joked that he should get an Oscar for acting. His voice mail filled with threats and mockery. “I wish they would have killed all you scumbags,” one caller said. Others threatened to rape and kill his mother and daughters. Trump reportedly called Fanone and the other officers “pussies.” Two days after the hearing, another cop Fanone knew who’d been there on Jan. 6 died by suicide—the fourth to take his own life since the riot.

For most Americans, Jan. 6 keeps getting further away. For Fanone, it’s still the only thing—the day his life stopped. And yet, as awful as it was, he’s grateful for it. “That’s, like, difficult to come to terms with. What if I had not gone through that?” he says. “I’d be the same dumbass that I was on Jan. 5. Not evil in my motivations. But ignorant to the truth.”

And so he keeps telling his story—the story of what really happened that day.

On the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, Mike Fanone woke up early, as usual, and went to the gym. He’d been living with his mom since a breakup left him with an apartment he couldn’t afford, working a second job at a security consultancy, saving for a down payment on a house for him and the girls—Piper, 9; Mei-Mei, 7; and Hensley, 5. Terry went to her prayer group, and when she came back she told her son she’d had a funny feeling and said an extra prayer for him.

Fanone’s shift was scheduled to start at 2:30 p.m. His plan for the day involved a heroin buy at the James Creek public housing project in southwest D.C. The buyer would be a longtime informant whom Fanone considered a friend, a 68-year-old Black transgender woman named Leslie. (Leslie, who suffered from cancer, AIDS and various addictions, has since died, which Fanone learned because he was listed as her emergency contact.) But shortly after noon, seeing what was happening in the news, he called off the buy and drove to the station instead.

Things were getting hairy. He had just hit the 14th St. Bridge when he heard the commander on the scene say on the radio that the department had run out of chemical munitions such as tear gas and pepper spray—not just what it had on hand at the Capitol but the whole department’s supply. In all his years on the job, that had never happened. A call went out requesting aid from surrounding jurisdictions.

At the station he met Albright, who was changing into his uniform. “What do you want to do?” Albright said.

“We’re going to go,” Fanone said. “Get us a vehicle.” He went to his locker and took out the uniform he’d never worn before, still in its plastic wrapping. He grabbed a tactical vest, a radio, a body camera, a helmet and a gas mask.

In the parking lot, a sergeant was tossing car keys to anyone volunteering to go to the Capitol. They parked a couple of blocks away. Fanone couldn’t figure out how to attach the gas mask to his vest, so they both left their masks in the car. It was eerily quiet as they approached the building on foot, passing abandoned police cars and barricades. Albright pointed out a trail of blood on the ground.

<strong>“What if I had not gone through that? I’d be the same dumbass that I was on Jan. 5. Not evil in my motivations. But ignorant to the truth.”</strong>They went in the south entrance and made their way to the columned chamber known as the Crypt, lined with historic statues and a replica of the Magna Carta. A couple of dozen trespassers were milling about. As the partners tried to figure out where to go, a 10-33 call—officer in distress—came over the radio from the west front of the Capitol. They went.

Some rioters had gone around and trickled in through other windows and doors, but it was this entrance, facing the White House, where most of the mob was trying to force its way in. Fanone and Albright came upon a narrow, stone-walled tunnel choked with clouds of gas. A commander in a gray coat was hunched over, retching, trying to wipe the tear gas from his face. Fanone saw that it was his friend Ramey Kyle. A dull roar was getting louder as they approached. “Hold the line!” Kyle shouted over the din.

Fanone and Albright went into the tunnel. The floor was slick with vomit. About 30 officers were pressed against a pair of brass-bordered double doorjambs, four or five abreast, several rows deep. The ones in front strained to push the crowd far enough from the doors to yank them closed, trying to lock their plexiglass riot shields together. But the rioters had managed to tear some of the shields away and were beating the cops with them.

From the back, Fanone and Albright could see the officers were ragged: injured, bleeding, blinded, fatigued. Some had been there for hours. They could also see that if the line broke, they would be trampled in the narrow tunnel, and the rioters would overrun the building. This was the last line of defense.

“Let’s get some fresh guys up front!” Fanone yelled. “Who needs a break?” Some officers pointed at colleagues they thought needed relief, but nobody volunteered to come off the line.

What makes a hero? Is it bravery? Is it sacrifice? Or is it the man who refuses to let us forget?

“C’mon, MPD, dig in!” Fanone yelled, bracing his hands against the other officers’ backs. “Push! Push ’em the f-ck out!”

He and Albright got to the front. It was only then that they looked out on the sea of people for the first time and saw what they were up against. The rioters were coordinating efforts, yelling “Heave! Ho!” and lunging in rhythm.

An officer yelled, “Knife!” and Albright turned to his left, away from Fanone, to grab the weapon. When he turned back Fanone was gone.

Read more: Inside One Combat Vet’s Journey From Defending His Country to Storming the Capitol

He was out in the crowd, surrounded by rioters. They dragged him face first down the stairs and punched and kicked and beat him. They ripped off his badge and took his radio. One kept lunging for his weapon. Someone was yelling: “Kill him with his own gun!” Fanone felt an excruciating pain at the base of his skull—the taser—and cried out, but he couldn’t hear himself scream. The rioters seemed intent on torturing him. He thought about pulling his gun. He would be justified in defending himself, but then what? He thought of his daughters. He didn’t want to die. “I’ve got kids!” he cried.

A couple of rioters surrounded him, fighting off others. “Bring him up, bring him up,” one said. “Don’t hurt him,” said another. “Which way do you want to go?”

“I want to go back inside,” he whimpered, and that’s the last thing he remembers. The rioters lofted his limp, unconscious body to the doorway—the battle line. Albright grabbed him and pulled him back through the phalanx.

One of the officers carrying Fanone back into the hallway shouted, “I need a medic! Need an EMT, now!” Albright followed, crazed with fear. “I got it. It’s my partner!” he yelled. “Mike, stay in there, buddy. Mike, it’s Jimmy. I’m here.”

What does Mike Fanone deserve? A parade? A key to the city? A White House ceremony? He’s not asking for any of that. He’s not asking to be called a hero—he just wants us to remember what his sacrifice was for. Fanone believes we can’t keep trying to outrun this thing; we’ve got to turn around and face it, defeat it once and for all. That if all we do is turn away and hope it fades, it will just keep getting stronger until it comes back to kill us all.

Fanone has gotten none of those traditional heroes’ honors. None of the officers have. But perhaps that’s normal. Perhaps we always fail our heroes: the veterans who sleep in the street, the whistle-blowers languishing in penury. Perhaps all the medals and ceremonies are our constant, insufficient attempt to atone. But we can never be grateful enough. For our comfort, for our safety, for our freedom.

They laid him down on a luggage cart—there were no more stretchers, no more ambulances. “Take his f-cking vest off, man. He’s having trouble breathing,” Albright said frantically. He took Fanone’s gun so that he wouldn’t come to and instinctively reach for it, thinking he was still out in the crowd.

“C’mon, Mike,” Albright pleaded. “C’mon, buddy, we’re going duck hunting soon.”

“Fanone, Fanone,” another officer said. “You all right, brother?”

The world swam blurrily back into view.

“Did we take that door back?” Fanone asked.

They took back the door. They defended the Capitol. That is the story Mike Fanone won’t let us forget.

—With reporting by Vera Bergengruen, Mariah Espada, Nik Popli and Simmone Shah