September 06, 2021 at 08:33AMNeha Thirani Bagri/Dalgaon, India

The way that her husband was snatched away from her in the middle of the night flashes in front of Mamtaj Begum’s eyes on idle afternoons.

It was a mundane day until then. Her husband Mahuruddin returned to their home in the northeast Indian state of Assam after selling fruit in a nearby town. He washed up, and they ate their dinner of rice and potatoes on the floor, by the table on which the children’s schoolbooks were piled high. At 2 a.m. they awoke to a commotion outside. In the dark, Begum could see about seven police officers gathered outside, surrounding their tin-roofed, one-room house. Four of them barged into the room, carrying large batons, ready to take Mahuruddin into custody. His offense: being unable to prove, in the eyes of the state, that he was not a foreigner.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Begum followed them to the police station with all the money they had at home, about $108, nearly eight months’ wages, and offered to pay the officer in charge in exchange for her husband’s freedom. When her offer was denied, she sat awake outside the police station all night. In the morning, she ran to a lawyer’s house and brought him back with her. But her efforts were in vain; as the sun reached the middle of the sky, police took Mahuruddin away to a detention center nearly 70 miles from their home.

“I was completely lost for a few days,” she says. “It felt like my world had fallen apart.”

Begum, who never attended school, hesitates when asked how old she is—either 36 or 37—but knows exactly how long her husband has been behind bars when she speaks to TIME. One year and nine days.

Creating a climate of fear

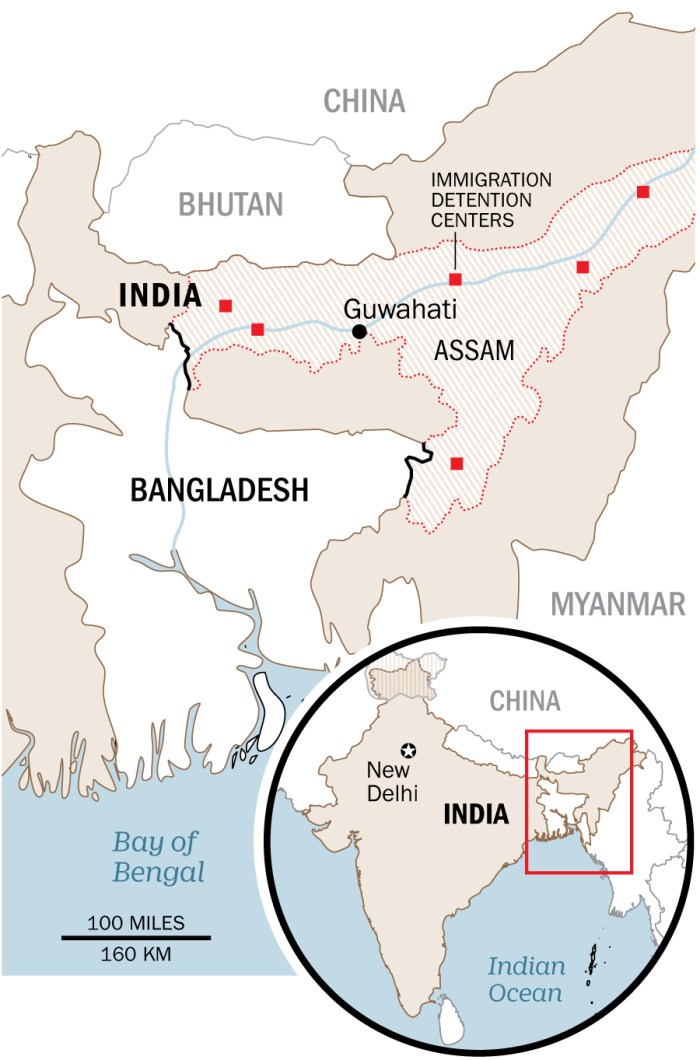

The divisive debate over who belongs in Assam, a hilly, ethnically diverse state in India’s northeast that shares a 163-mile border with Bangladesh, stretches back more than a century, to when the first waves of migrants arrived to work on the sprawling British tea plantations. The state’s population grew throughout the century, inspiring a vocal movement of Assamese citizens against Bengali-speaking migrants.

This culminated in 1985 with the signing of the Assam Accord, which said anyone who entered the state after March 24, 1971, the day before neighboring Bangladesh gained independence, is considered to be in India illegally and must be deported. Since then, the state of Assam and the national government have introduced a complex, overlapping web of measures to determine who is a legal citizen and who is not.

It is this web in which Mahuruddin and many others are now caught. When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in the state in 2016, it intensified efforts to weed out so-called illegal immigrants in Assam. As part of an exacting citizenship test, all 33 million residents of Assam had to provide documents proving they or their ancestors were Indian citizens before March 1971. When the National Registry of Citizens (NRC) was finally published in August 2019, it excluded nearly 1.9 million people. They now live under the threat of being ruled noncitizens by opaque foreigners tribunals and detained indefinitely.

While the citizenship registry purports to target all undocumented immigrants regardless of religion, the crackdown under way in Assam has disproportionately affected Muslims, who make up 34% of the population. The tribunals tasked with identifying legal citizens of India have tried significantly more Muslims and declared a much greater proportion of Muslims to be foreigners, according to a 2020 report by Human Rights Watch.

Human-rights observers and families of the detained now fear that Modi’s BJP has turned an anti-immigrant movement to identify and deport mostly Bengali-speaking migrants into a project to disenfranchise and create a climate of fear among Assam’s 10 million Muslims.

The government has moved to protect some 500,000 Bengali Hindus and people of other religions left off the citizenship registry. Months after it was published, the Indian government enacted the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which gave fast-track citizenship to many immigrants in the country illegally who are Hindus or members of five religious minorities—though not Muslims.

READ MORE: Here’s What to Know About the Citizenship Amendment Act

“For Muslims, even if we have all our papers we are foreigners,” says Begum. “If there is no mistake in our documents, even then we are declared foreigners. This is being done to us because we are Muslim.”

The experience of Mahuruddin—in perpetual limbo, with little opportunity to fight his case—could be a preview of what lies ahead for at least some of the 1.9 million people who were left off the National Registry of Citizens in Assam and are now waiting to hear what will happen to them.

His family, and those of dozens of others labeled noncitizens under existing laws, told TIME stories of children dropping out of school as parents struggled to pay legal fees, crippling poverty resulting from mounting debt, and the pain of families being separated. The economic, social and psychological impacts of India’s crackdown on illegal migration are felt acutely by those on either side of the prison bars.

Some observers are drawing parallels between the situation for Muslims in Assam and those of the predominantly Muslim Rohingyas who lost their citizenship rights in Myanmar as a result of a 1982 citizenship law—despite decades living in Myanmar. “There’s been no such process of this scale of creation of statelessness by states in modern times,” human-rights activist Harsh Mandar told TIME. “This would be creating a Rohingya-like situation where millions of people will be rendered stateless and will have to live as second-class citizens.”

What is happening in Assam could also offer the government a blueprint for similar moves across the country. India’s powerful Home Minister Amit Shah, who has previously referred to illegal migrants as “termites,” said in 2019 that the Citizenship Amendment Act would be put in place before the National Registry of Citizens was implemented nationwide.

Although experts say it would be practically impossible for the government to incarcerate or deport all of the country’s 200 million Muslims, these laws could be used to create a Jim Crow–like system of mass disenfranchisement for Indians of Muslim faith.

“Industrial-style incarceration detention for millions of citizens rendered noncitizens is a virtual impossibility in India because we are not dealing with 2 million Muslims, we’re dealing with about 200 million Muslims,” said Ashutosh Varshney, the director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University.

He argues the BJP’s immigration enforcement will lead to mass disenfranchisement akin to the Jim Crow laws of the American South, under which Black Americans were deprived of their voting rights through the use of literacy tests, poll taxes and other measures.

‘The nowhere people’

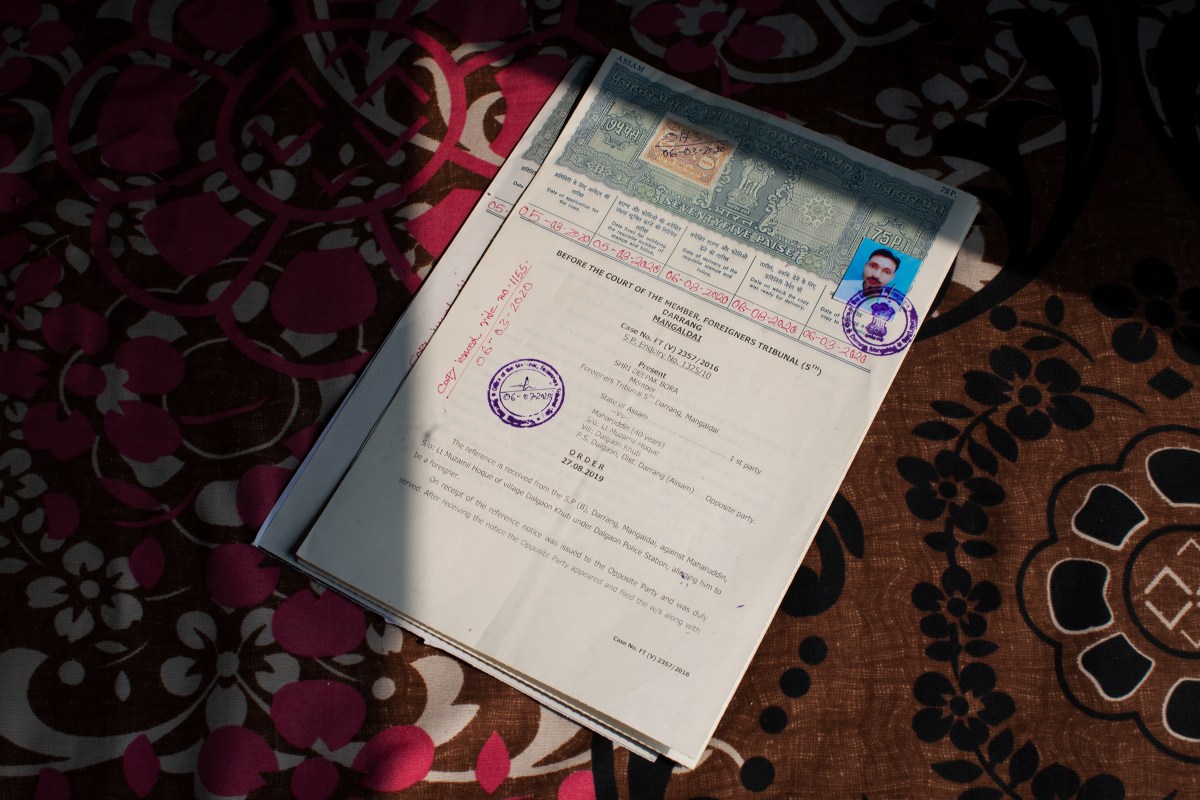

In November 2018, Begum’s husband Mahuruddin received a notice that he was suspected of being a foreigner. Within a matter of weeks, he was told to appear in front of a foreigners tribunal with documents proving his citizenship. These quasi-judicial bodies are unique to Assam, and the primary means of determining who is a citizen in the state. The courts place the burden of proof on the people accused of being foreigners, many of whom are poor and illiterate, unable to navigate a convoluted system or afford legal representation.

Mahuruddin gathered all the evidence he could find, including the Aadhaar card with his official Indian identity number, his voter-identity card and his tax-identity card. The couple spent two years presenting their evidence to the tribunal, but it finally ruled that Mahuruddin was not a citizen. They appealed the judgment in the state’s High Court, but the appeal was rejected. It was a week later that officers barged into their home and took Mahuruddin away.

In the year since, Mamtaj Begum has visited several local government offices, carrying a fraying pink folder with her husband’s papers. The money she had collected for her daughter’s wedding has gone toward lawyer’s fees, nearly $1,240 so far. As the country went into a nationwide lockdown in March 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19, little work was available. She washes dishes and cleans homes for a meager $14 per month. Her son, 16, who was attending private school, has dropped out and now takes on sporadic work at shops in town.

The lawyer Begum hired managed to secure a bail order for Mahuruddin in March, but after weeks of Begum chasing after the required signatures, she was told that there was a mistake in the order and her husband could not be released. As the cool winter afternoons turn to sweltering summer days, she has begun to lose hope.

“I have all these papers, but yet they say he is not an Indian,” says Begum, feverishly flipping through her folders for the hundredth time. Tucked inside a book by her bedside is a faded photograph of her husband with his son and nephew, the only one she has of him that is not a passport picture. “If I didn’t have any documents, then I can understand if they caught him. But we have everything—yet they took him. What should I do?”

In Assam, the citizenship registry is only the latest process by which the state identifies suspected foreigners. There are two other initiatives, which work in parallel and can sometimes even result in different outcomes for the same people. One, which was started by the election commission in 1997, allows an official in the local government to flag people on voter rolls as doubtful voters, or “d-voters,” thereby revoking their right to vote.

The second is through the Assam Police Border Organization, a border police force unique to Assam that was established in 1962. Here, a police constable can declare a person is a suspected foreigner based on tips from their neighbors. This is how Mahuruddin was sent before a foreigners tribunal.

These two processes have continued during the pandemic, with more people marked as suspected foreigners over the past year and sent to detention centers, according to lawyers and activists based in Assam—though official statistics are not publicly available. People singled out by either process must appears at a foreigners tribunal to prove that they are Indian citizens.

Assam has not yet begun trying to deport people left off the citizenship registry. Those caught in the current crackdown, like Begum’s husband Mahuruddin, were labeled noncitizens through existing laws. But two years after the list was published, the government has also not handed out formal rejection notices, which would detail the reason they were deemed foreigners and allow them to appeal their exclusion. Following the party’s re-election to state government, officials have been questioning the integrity of the existing citizenship registry and are demanding a redo. “The BJP clearly was not happy with the NRC,” says Sanjib Baruah, a professor of political studies at Bard College in New York and the author of a book on Assam’s anti-immigrant history. “When it became clear that at least half of the people who were found to be noncitizens are Hindus, that shook them up.”

Assam residents who are declared illegal immigrants technically face deportation, but officials from Bangladesh have repeatedly said they will not accept those left off Assam’s citizenship registry, and have accepted only a small percentage of people declared foreigners by the tribunals. In total, only 227 people have been deported to their country of origin—most of them to Bangladesh—between March 13, 2013, and July 31, 2020.

With little opportunity to appeal in a complex legal system and Bangladesh refusing entry, some have spent years behind bars. Momiran Nessa, whose case gained national attention, was held in jail for nearly a decade after she was declared a foreigner. She was finally released in 2019 after a Supreme Court order that allowed bail for those who had been detained for three years. That has since been reduced to two years in an effort to contain the spread of COVID-19 in prisons.

“Without the right of citizenship, countless will be dispossessed. They will become the ‘nowhere people,’ refugees in their own land, without rights, entitlements or legal protections,” says Angana Chatterji, the author of a book on Hindu nationalism and a human-rights expert at the University of California, Berkeley.

Life on the inside

It’s an overcast March afternoon at Goalpara district jail when Samiran Nesa arrives in an auto-rickshaw. The air is heavy with humidity after thunderstorms the night before. A red plastic folder peeps out of her pink purse, carrying the important documents related to her husband’s case. She started from home with her father at 8 a.m., and they took a little over three hours to reach their destination. She sits in the waiting area, turning her phone over and over in her hands. A frazzled man next to her, waiting to meet his younger brother, is asking anyone who will listen how to secure bail for his brother.

Finally, when the gates open at noon and Nesa sees her husband Sohidul Islam through the iron bars, she wells up and is unable to speak. He looks at her, averts his eyes. Nesa jostles with about two dozen other visitors lined up outside the jail windows. They are separated from the detainees by a wire mesh, iron grills and a metal fence. A cacophony of simultaneous conversations fills the air.

Islam threads his fingers through the wire and presses his face against the metal, wiping his tears on his sleeve. He asks after his children, ages 15, 17 and 18. Finally, Nesa speaks up and inquires about her husband’s health, her voice strained. He has been having abdominal pain and feels faint on some days.

The months in prison have made him weak and thin. Nesa asks if he managed to cook the vegetables she brought last time, as they are not allowed to give the detainees cooked food. They discuss the state elections—which the BJP won in April. He asks if they felt the storm at home as well. “The days feel very long here,” says Islam. “It is hard to pass the time.”

Soon it is time to go, and as Nesa watches her husband turn and walk back through the prison arches, she wipes her eyes on her red scarf.

Nesa and her family are shocked by her husband’s case because the entire family was included in Assam’s National Registry of Citizens. However, in 2019 before the citizenship registry was published, a notice came to their home in Kalgalchia, Assam, saying that a case had been registered against her husband nearly two decades ago when he was working in Guwahati, Assam’s largest city. “How did he suddenly become a foreigner?” asks Nesa. “He was born here only; how could he have come here after 1971?”

They fought the case for six months at a foreigners tribunal in Guwahati, nearly 75 miles from their home. When they called Islam’s father as a witness, he got flustered in the intimidating courtroom and hesitated in his testimony. According to documents viewed by TIME, the court ruled that Islam could not prove a link to his paternal grandparents, which was essential in proving that the family was in Assam before the cutoff for citizenship in Assam. On Dec. 30, 2019, the court ruled that he was a foreigner. Islam’s son, Hashmat Ali, was at school when his father called him and told him he was being taken to prison. The 17-year-old ran all the way home, tears streaming down his face.

Islam’s detention has devastated his family. Both of his sons have had to leave their studies and take jobs, one in a tile factory and one as a security guard. For the first time in her life, Nesa has taken up work outside the home, cleaning classrooms in a nearby school. “I miss him a lot, he is in there, and I am sleeping here,” says Nesa. “Even when I dream, I dream of the jail lockup.”

Detention centers for migrants—which are located inside existing prisons—have been functional for over a decade and were first built in Assam in 2009 when the state government was headed by the Indian National Congress, now India’s main opposition party. Currently, there are six detention centers with a combined capacity of 3,300 people—though they house just a small fraction of that number.

The conditions faced by those held in detention centers have been the subject of growing concern in India. In January 2018, Mandar, the human-rights activist, visited two of Assam’s detention centers as a special monitor for minorities for India’s National Human Rights Commission. Later that year, Mandar resigned from the position and took his findings public, saying the commission did not act on his report.

“They were really hellish places,” Mandar tells TIME. The detainees he saw lived in confined spaces with no prospect of release. Families were brutally separated and parole was not allowed, according to Mandar’s findings. Detainees were not allowed to work, a right afforded to prisoners convicted of serious crimes. “They create a kind of dread in the heart of every person whose citizenship is contested.”

Crucially, as well, all but the most serious criminal convicts have sentences with a definitive end date, after which they will be released. For those declared noncitizens, it remains less clear. India’s Home Ministry, which oversees citizenship rules, did not respond to TIME’s written requests for comments.

Begum, whose husband is in the detention center inside Tezpur jail, says his stay in prison has changed him. Previously a healthy, fit man, he now looks gaunt and shrunken. “He is not the same man he was when he went in,” says Begum.

When Begum goes to visit Mahuruddin she carries puffed rice, cooking oil, cookies, vegetables and fish when she can afford it. In prison, her husband is given Assamese tea and roti in the morning, some rice and vegetables at 11 a.m., and then dinner at about 4 p.m., after which the detainees are locked in their cells for the night.

On her visits to the Tezpur jail, Begum noticed a pattern in the detainees who were in prison for being “foreigners.” “There are mostly Muslim people in jail for this issue, this is what I have seen when I go there,” says Begum. ”There are not too many Assamese Hindus or Bengali Hindus.”

But detainees caught in Assam’s citizenship crackdown will not be held in prisons much longer. Because of the attention brought to the conditions in detention centers by activists like Mandar, detainees will soon be moved out of India’s prison system into detention centers specifically built to hold illegal immigrants. Following a petition filed by Mandar in India’s top court, the Indian government circulated a detailed manual on how to build a “model detention center” in January 2019. Under the guidelines, families would not be separated and detention centers would have a crèche and a skill center.

One of these “model detention centers” is being built in Assam’s Goalpara district—a sprawling construction site spread over six acres, bounded by thick, towering boundary walls painted red. The compound, which will include a hospital and separate sections for men and women, will have the capacity to hold 3,000 people when it is finished.

“The new detention center itself would be an apparatus to create fear,” says Anjuman Ara Begum, a human-rights researcher based in Assam. Its capacity may sound small, she says, “but it would create a deep fear among vulnerable Bengali Muslims or Bengali Hindu people.”

Assam is not alone in building detention centers for illegal immigrants. At least five other sites are being constructed across India, in addition to ones that are already operational in Delhi, Karnataka and Goa. On Aug. 17, the Assam state government altered the formal term applied to detention centers, stating that they were to be called “transit camps” from now on.

Flawed justice

At the center of the citizenship tangle are the foreigners tribunals. First set up in 1964 to appease growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the state, the tribunals—which number more than 100—have been repeatedly found to be riddled with flaws. According to government data, nearly 87,000 people were declared foreigners in Assam from 2015 to June 2020—though most were tried in absentia and only a small fraction have been detained.

A 2019 investigation by Vice, based on judgments from five courts and interviews with nearly 100 people, found that the percentage of people found to be illegal immigrants varied greatly from tribunal to tribunal. About 75% of the decisions were issued in the absence of the accused. In some cases, individuals who were declared Indian citizens were summoned again by the same tribunal. Nearly 9 of 10 cases that were brought in front of the courts were against Muslims, who were also disproportionately declared illegal immigrants.

Aman Wadud, a human-rights lawyer in Assam who has argued many cases in front of foreigners tribunals, tells TIME that since the BJP took control of the state in 2016, rulings have “become much more arbitrary.”

Wadud says courts have routinely declared people to be foreigners even when applicants provided more than a dozen documents, where previously four or five would suffice. A report by Amnesty International found that many were found to be noncitizens because of inconsistencies in documents, which was common because of a general lack of good record-keeping in the state. Spelling mistakes have also led to some being ruled foreigners, according to a report by Reuters. Assam’s Home & Political Department, which oversees foreigners tribunals, did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2020, the New York Times interviewed one current and five former members of the foreigners tribunals, who act as judges in the courts. Tribunal members told the Times they felt pressure to “find” more foreigners and declare more Muslims to be noncitizens. In three cases, members said that their jobs were contingent on this and that they were fired because they did not declare enough people as foreigners. In 2017, some former tribunal members sued the state government for wrongful dismissal, but lost the case.

Access to legal representation to navigate this byzantine system can make all the difference for those fighting citizenship cases. Often the socioeconomic background of those accused of being foreigners means they cannot afford expensive legal fees. “A disproportionate number of persons who have been and may be declared stateless are Bangla-descent Muslims from marginalized social classes,” says Chatterjee, the University of California, Berkeley, human-rights expert. “They often lack the support systems, information and resources to seek recourse and challenge the decision.”

Nur Hussein is among those few who were able win their cases after being declared foreigners by a tribunal. In June 2019, Hussein and his wife Sahera Begum were arrested and sent to the detention center in Goalpara after being declared foreigners. They spent a year and a half in the prison along with their two young children until an appeal in court established that they were Indian citizens. The hardest part about the time in jail was that Hussein was separated from his wife and children, who were held in the women’s section of the prison. Sometimes, at mealtime, he could see them at a distance.

“They give you a plain cloth to sleep on,” said Hussein, his voice shaking. “When someone dies, they wrap up the body in that same cloth and send it away.”

Hussein was able to prove that he was a citizen of Assam by providing documents that showed that his grandparents’ names were included in the state’s 1951 citizen registry and his grandparents’ and father’s names were included in electoral rolls from 1965, long before the cutoff date in 1971.

Unlike many others, he was able to win his case because he was able to access pro bono legal aid. “I feel like I was in hell and I have returned to the world,” says Hussein.

Different results for Hindus caught in the crackdown

For all its flaws, the system of rooting out foreigners is not uniformly unfair. After Bengali-speaking Hindus were caught up in the citizenship dragnet in Assam, the BJP-led government has worked to ensure that they have a way out through the Citizenship Amendment Act, which gave non-Muslim immigrants a path to becoming citizens.

The consequence, says Sanjib Baruah, the professor of political studies at Bard College, has been to effectively redraw the definition of who belongs in India along religious lines: “Since Hindus by definition cannot be illegal immigrants in India, illegal immigrants [in Assam] can only mean Bangladeshi Muslims.”

Through the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act, the Indian government would in effect be using the rule of law to discriminate against Muslims, a move that many legal experts have argued is unconstitutional. The bill sparked massive protests across India, which finally came to an end because of the nationwide lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. India’s constitution, which was read aloud at protests against the law across the country, guarantees equality and explicitly enshrines secularism. While India has long been touted as the world’s largest democracy, Sweden-based V-Dem Institute said in its latest report that India has turned into an “electoral autocracy.”

READ MORE: Inside the Anti-Citizenship Act Protests Rocking India

While protests against the announcement of the citizenship law raged on the streets of Assam, inside Goalpara district jail, Hindu detainees celebrated. Arun Shutradhar, who was among them, chuckles as he remembers the hopeful mood—people prayed, sang and beat drums. Shutradhar was sure that the new law would solve his problems.

Shutradhar discovered in June 2017 that he had been marked as a doubtful voter. He submitted his papers, unaware that he had already been declared a foreigner by a tribunal in his absence. In March 2019, he was arrested and taken to an immigrant detention center.

“I felt like suddenly I did not exist in the country,” says Shutradhar. “I have never committed any crimes, but now I find myself in jail.”

During the two years he spent behind bars, nine detainees who were being held as foreigners died “out of tension,” he says. As COVID-19 spread across India, many in his detention center got sick with the disease.

As a Bengali Hindu, Shutradhar says he was a minority in the detention center. For every 10 Muslims, he estimates there were four Hindus like him. When his wife Shivani visited and asked him whether he lived with Muslim people, he fibbed to calm her nerves, telling her Hindus and Muslims in jail lived separately. Decades of xenophobic fearmongering has created a deep mistrust between members of different communities in Assam.

Shutradhar was finally released on $68 bail in April after a judge ordered all detainees who had been in jail for two years released to reduce overcrowding amid the pandemic. For now, Shivani is happy to have her husband back home on bail. “On television, Modi-ji was giving speeches in support of Hindus, announcing a new bill to protect us,” says Shivani, using a common honorific to refer to India’s leader. She believes her husband will soon be free for good. “Being a Hindu, at least I can believe that we will not face trouble under this government,” she says. “What he says on television, we are dependent on that.”

Giving people access to justice

The people swept up in Assam’s dragnet are not completely abandoned to their fate; lawyers and human-rights activists have come together to attempt to provide legal aid to those whose citizenship is contested. There are now about eight “constitution centers” scattered throughout the state that serve as legal-aid clinics for those who cannot afford representation. Volunteers attached to every constitution center are trained to provide basic legal aid to people who are fighting citizenship cases. The centers hold workshops, are stocked with a small library of books about the constitution, and raise funds for those who cannot afford lawyers.

“People must also know the basic rights they have—that everyone should be treated equally, that the constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty,” says Wadud, co-founder of the Justice and Liberty Initiative, which provides pro bono legal aid to people on citizenship cases and is spearheading the constitution centers. “We are trying to build infrastructure where people have access to justice.”

For Mamtaj Begum, the future remains uncertain. As further proof at how erratic Assam’s anti-immigration policy is, her husband Mahuruddin, who remains behind bars after being declared an illegal immigrant, was included in Assam’s National Citizenship Registry—while Begum and her son were left off the list.

With the status of the current list in limbo, it’s unclear when or if Begum will be hauled in front of a tribunal and potentially detained. It also means her husband will get no reprieve for being found to be a citizen.

But Begum is too preoccupied with her present troubles to worry about the prospect of going to a detention center herself. “I don’t have any tension about whether they will take me into jail,” she says, shaking her head, her words tumbling over one another. “If my husband comes home he will be able to earn and feed our children. I am struggling to do that. I don’t think about the future, I just want to bring my husband home.”

The independence that has been thrust upon Begum since her husband was detained has made her braver. Earlier, as someone who never worked, she spent most of her days confined to her home and felt afraid to go into town alone. Now, she travels around the state by bus, visiting her lawyer, the prison where her husband is being held, the state high court, various government offices, the homes where she works as a cleaning lady, and the construction sites where she sometimes finds daily wage work.

She says that when a border police officer stopped her recently and asked why she was not afraid of him, she told him she had nothing to fear. “He is also a human,” exclaims Begum. “He got a job and wore a uniform, so he is catching people and taking them away. What is there to be afraid of?”

But in quiet moments of reflection, Begum feels very alone. Though her brother-in-law tries to help her and sometimes sends rice and wheat, he is also struggling to support his family.

“No one asks after me if I have eaten or if the children have eaten,” says Begum. “I feel like I am neither alive nor dead. The days are just passing.”

—The reporting for this story was made possible by a grant from the South Asian Journalists Association