August 09, 2021 at 11:13PMChris Wilson

For the first time since April, when the U.S. lost its appetite for COVID-19 vaccinations, the rate at which Americans are showing up for their first dose is consistently on the rise. This uptick, while present to some degree in most states, is heavily driven by regions that are experiencing the most dramatic increases in new infections.

There are no two ways about it: For all the increasingly desperate incentives that states have offered, the strongest motivation for vaccine-hesitant Americans to date is the presence of a resurgence of COVID-19 in their region.

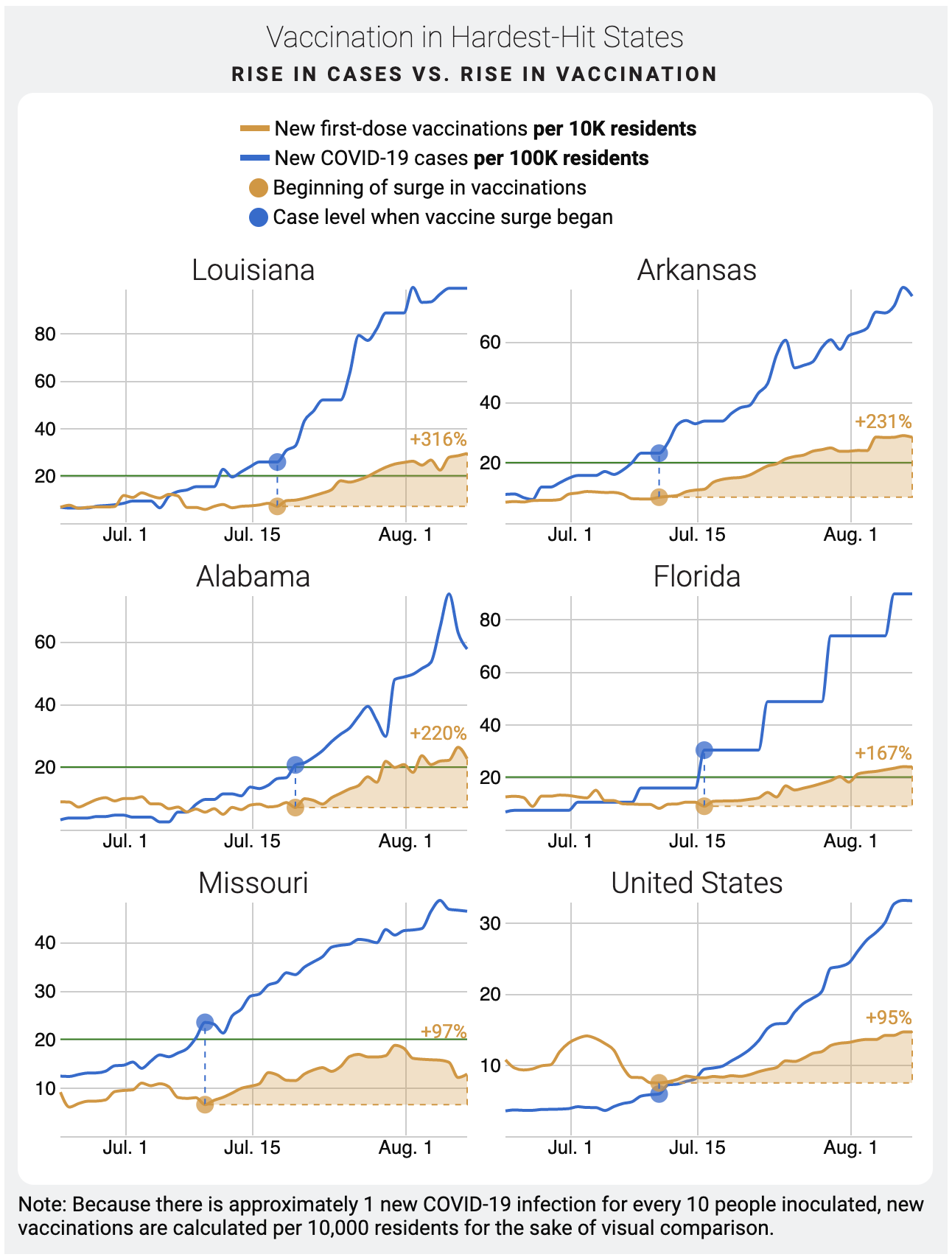

Nationwide, the number of people receiving a first dose each day has nearly doubled since July 11, when that figure stood at 7.5 new doses per 10,000 people. It is now 14.6, as of Aug. 8. But compare that 95% increase to these five states where cases have dramatically surged since the fourth wave of the epidemic took off in the U.S.:

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

As these charts show, the uptick in residents getting their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccination is much higher than the U.S. average in regions in the South that have seen the largest spikes in new infections, and which have typically lagged well behind national vaccination rates. The closest of these states to an exception is Missouri, whose renewed interest in vaccinations briefly spiked but has since drawn back—though remains double what it was at its most recent nadir.

In each case above, TIME identified the date at which the uptick in new vaccinations began, based on a simple calculation of when the figure first significantly increased over a 10-day period. While this definition is somewhat arbitrary, it captures the rise most precisely (based on extended trial and error) because, in many cases, the rise began very gradually and didn’t take off for days or weeks.

What’s most curious here is that, in all cases, it appears that the uptick in new vaccine recipients began when the case rate, calculated (like vaccinations) on a rolling seven-day basis, rose above 20 new infections per 100,000 people—the green line in the graphs. If that doesn’t sound catastrophic, consider that, at its worst peak in early January 2021, the national rate was 76.5 per 100,000, and that the resurgent cases this summer didn’t pass 20 for the country at large until July 29. As recently as July 5, the national figure was under 4.

In all the states visualized above, the fourth wave arrived early and has reached far greater heights than the national rate. In Louisiana and Florida, the fourth wave is already worse than the third, last winter. Alabama and Arkansas are likely to reach new peaks within the week.

The national vaccination rate is most often reported as the percentage of Americans who have received a completed dose of the vaccine, which currently stands at 50.1% after weeks of stubbornly refusing to surpass the halfway mark. Given that the vast majority of all COVID-19 vaccine recipients receive either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna varieties, which require two doses several weeks apart, we don’t expect to see a noticeable rise in the completed rate for at least another week—assuming new recipients in these newly vaccine-tolerant regions show up for their second dose, which is not universally the case.

While five states do not make a trend, a review of all 50 and Washington, D.C. show early signs of similar patterns outside of the hard-hit South. COVID-19 case rates are rising everywhere, but many states remain below the 20 mark or only very recently passed that apparent threshold. The rates of new vaccine recipients are likewise on the rise in most regions, particularly in states where they lagged well behind the national average prior to this most recent resurgence.

If this pattern holds as more and more regions experience intolerable spikes in new cases, there is a good possibility that a bad situation could have a positive side effect as the vaccination rate receives, well, an adrenaline shot after months of crawling only incrementally upward.